23 December 2021

By Nina Martineck

Most of us know the former P.S. 64 as CHARAS/El Bohio, a community center started by the group CHARAS in 1979. However, the feasibility and productivity of this community center relied not only on the tireless efforts of CHARAS and associated members, but also directly to the architecture of the space as designed by master school architect C.B.J. Snyder. The architecture itself enabled CHARAS to use the former school as a community center, as this program was a sub-intent of Snyder during his design process. The most notable attributes of this intent were his development and use of the H-plan and the half-sunken auditorium.

C.B.J. Snyder served as the first Superintendent of the New York Board of Education between 1898 and 1921. During his tenure, he designed or modified over 400 schools across the newly-established five boroughs. In seemingly banal ways, he revolutionized school design, taking notice of each scale, from the composition of the building’s windows to the arrangement and varnishing of the students’ desks.(1) Public School Number 64 in the Lower East Side was no exception.

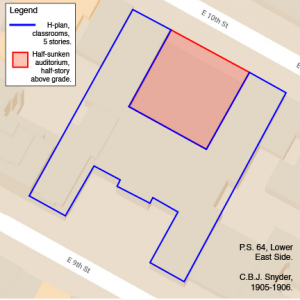

As the second wave of immigration hit, the Lower East Side became one of the densest neighborhoods in the world. As the population dramatically increased and new laws mandated school attendance for children up to age sixteen, the city faced a shortage of school space.(2) During this period, Snyder built nearly a hundred new schools, including P.S. 64. In a controversial move, he employed the newly-standardized H-plan, which would cut through an entire city block and occupy the footprint of about ten tenement buildings.(3) Real estate developers saw this as a loss of profit, since a large portion of the school’s land would be left empty for courtyards. Progressive reformers, however, believed that this varied use of the city block, the purposeful designation of space for light, air, and play, would alter the neighborhood’s fabric for the better.

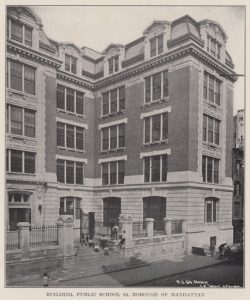

Quite simply, the H-plan refers to a building in the shape of an H. A center bar connects two wings, and this shape built on a rectangular lot creates two voids, which can be used as courtyards. The classrooms face inward toward these courtyards, which insulates them from noise and exposes them to better daylighting. Snyder ensured that his facades would be at least sixty-percent glass, which further improved the classrooms’ lighting.(4) In a move popularized by the famed Louis Sullivan, a member of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) at the same time as Snyder,(5) these schools’ frames were steel, which not only allowed the sixty-percent glass goal to be met, but it drastically decreased schools’ construction time, enabling them to nearly be mass-produced. The form of the H-plan lended itself nicely to the column-grid system required for steel construction. The first of Snyder’s H-plans, P.S. 165 was photographed and praised by none other than Jacob Riis during his study of immigrant neighborhoods. In his writing, Riis declared, “I cannot see how it is possible to come nearer perfection in the building of a public school.” (6)

P.S. 64 is the only extant example of Snyder’s work with the French Renaissance Revival style.(7) The copper mansard roof, a telltale move of the style, provided fifth-floor classrooms with the lofty ceilings needed for workshops or gymnasiums. Rows of barrel vaults supported high ceilings on the other floors, which further increased daylighting and improved ventilation. On the second floor, classroom sizes could be adjusted with movable partitions. Wide staircases fostered congregation in addition to circulation, giving students places to interact beyond the classrooms.

P.S. 64’s H-plan was exemplary, but Snyder employed another new tactic on this school: the half-sunken auditorium. The northern void of the H, off of Tenth St., is actually a half-story above-grade. Underneath the courtyard, which is still fully accessible to children from inside the school, is the auditorium. It’s partially underground, lit by glass blocks along the ceiling. Unstriated Corinthian columns support a coffered ceiling, aesthetically-conscious methods of offsetting the lack of ceiling height resulting from its partially-underground position. Wood and metal seats were nailed to the hardwood floors, slightly offset from each other.(8)

Not only did tucking the auditorium into the space outside the H let more classrooms have more direct sunlight, but the positioning allowed it to be accessible to the public without requiring them to go through the school. On E Tenth St., the greater community could get into the auditorium for programs like lectures, meetings, or educational programs for immigrants. New York Mayor Jimmy Walker and President Franklin Delano Roosevelt both spoke in P.S. 64’s auditorium. The New York Board of Education sponsored a lecture series that covered everything from the Rocky Mountains to the prevention of tuberculosis. Local actors performed free renditions of Shakespeare plays on the auditorium’s stage. Groups held meetings, and social workers taught English not only to the children, but to their parents as well. The auditorium was even heated by a completely disparate ventilation system, as Snyder knew that it would be on a different schedule than the rest of the school and therefore require different accommodations.(9)

With this careful move, Snyder maintained his stance that schools belonged to the entire community, not only the children who attended. The school becomes a social institution, not solely educational. With Snyder’s H-plan and sunken auditorium and the combination present in P.S. 64, we watch the school building take on a new purpose: a community center.

In a way, schools have almost always served a role in building and maintaining the communities of which they are part. Laura Ingalls Wilder, a pioneer teaching in South Dakota, recounts a town meeting-turned-spelling bee in De Smet’s one-room schoolhouse. In Ireland, schoolhouses often doubled as churches. Since the inception of schools, people have been assigning other uses to the building. But Snyder’s plans are calibrated. His reasoning is impeccable. Community use of the building is the intention, not a side effect. Future school planners, including Juan O’Gorman in Mexico and Loren Rand in Spokane, Washington would apply these concepts in their school designs, using the buildings as epicenters for communities who needed them.

In 1977, due to low enrollment, the City of New York closed P.S. 64 and relocated its 844 remaining students to the new P.S. 64 on E Sixth St. The building sat vacant until 1979, when CHARAS occupied it and began its transition into CHARAS/El Bohio. Snyder’s architecture immediately took to this new program, as the building’s use as a community center was always its intention.

CHARAS’s cultural celebrations and outside programming took place in the H-plan’s voids, away from the streets. The fifth floor’s lofty ceilings housed large puppets, a staple of Puerto Rican culture. The stairwells accommodated new generations of students gathering before workshops and programs. Large spaces like the cafeteria were perfect for after-school programs, the ample lighting provided by the large windows allowed the building to operate before it could be electrically lit, and the inward layout of the classrooms created an escape from the rest of the city. As the neighborhood shuddered, it leaned on CHARAS/El Bohio, welcomed in by both the unyielding efforts of CHARAS and the attentiveness of Snyder’s architecture.

The half-sunken auditorium in and of itself enabled the building’s seamless transition into a community center, as that was the program it was always intended to serve. Because it was designed to be fully accessible to the public, CHARAS could use it for community programming. Then little-known filmmakers like John Sayles and Spike Lee premiered their projects there, and local theater troupes like Great Small Works and Ache Dance Company rehearsed and performed in the space.

P.S. 64 still has students, as it always has. They learn outside the building, the school itself their teacher. They aren’t privy to the novelty of the effervescent classrooms, as the second wave of immigration may have been. They did not experience the neighborhood’s tribulations from the sturdy yet fading walls as third-wave immigrants and early hipsters did. They weren’t there when CHARAS rebuilt the community and its center, although they were built alongside it, their legacy secured by a school they would only know as some not-so-ancient ruin.

Communities and schools are inextricable. Even when a school is condemned to vacancy, it will inevitably continue to fulfill its purpose. C.B.J. Snyder must have known this to an extent, even if he had no way of knowing what additional programs his school would come to serve: quiet rebellion, unfathomable resilience, and unyielding loyalty.

Herein lies the beauty of buildings like P.S. 64–not knowing exactly what they will do next. We only know this: Regardless of where the Lower East Side goes, whoever moves in and sprinkles their culture into the melting pot, whatever the rest of the world decides to throw at the people dangling from fire escapes and clinging to who they promised they would be, P.S. 64 will stay put. The community built their anchor and moored themselves. Just as P.S. 64 taught them, they aren’t moving anytime soon.

Notes:

- C.B.J. Snyder, “The Lighting of School Rooms,” page 109. The American Architect, Vol. 108. July 1908. Accessed 17 October 2021.

- Moses Stambler, “The Effect of Compulsory Education and Child Labor Laws on High School Attendance in New York City, 1898-1917.” History of Education Quarterly 8, no. 2 (1968).

- Based on the standard dimensions of a turn-of-the-century dumbbell tenement and 1914 zoning map.

- “The Lighting of School Rooms, “ page 107.

- American Institute of Architects, “AIA Historical Directory of American Architects.” Accessed 20 August 2021.

- Jacob Riis, The Battle with the Slum (New York: Macmillan Co., 1902).

- Landmarks Preservation Commission, “(Former) Public School 64.” June 20, 2006. Accessed 20 August 2021.

- “PS 64, Manhattan: public lecture.” BOE: Board of Education Archives. 1910. Accessed 12 November 2021.

- C.B.J. Snyder, “Public School Houses in the City of New York.” Modern School Houses (New York: Swetland Publishing Co., 1910).